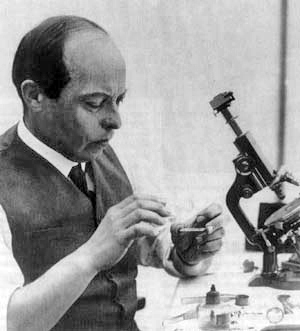

Despite the repression of successive political regimes in Russia throughout the 20th century, many acclaimed animations were crafted by gifted Russian animators like Wladyslaw Starewicz, who produced the first animated shorts to use puppets to drive the narrative. Until then, the use of stop-motion had been largely confined to special effects, famously Georges Méliès' 'A Trip To The Moon' ('Le Voyage Dans La Lune' 1902). Starewicz was also a technical pioneer, combining live-action and stop-motion in films such as 'The Mascot' ('Fetiche Mascotte' 1933). Similarly, the first full-length stop-motion animated feature film 'The New Gulliver' ('Novyy Gullivyer' 1935) directed by Soviet animator Aleksandr Ptushko, was also the first of its kind with sound.

Post October Revolution, media that expounded themes of socialist realism became increasingly prevalent in the new Soviet Union. Artworks deriving from folklore or adaptations of fairy tales were popular, often presenting proletariat heroes in bucolic scenes. However, when in 1932 the Stalinist regime transformed preference into policy [1], freedom of artistic expression was curtailed and media subsequently policed. Henceforth, animated productions were commissioned for the purpose of Soviet propaganda.

In 1936, the Soyuzmultfilm animation studios [2] were founded. From a few small workshops, the organisation rapidly grew into the premier animation studio in the Soviet Union. After the death of Stalin in 1953, the studios began to diversify beyond cell animation into cut-out and stop-motion animation, setting up a 'puppet division' the following year. As the reins of Sovietism relaxed over the next 30 years, some internationally acclaimed films such as 'Island' ('Ostrov' 1973) directed by Fyodor Khitruk and 'Tale Of Tales' ('Skazka Skazok' 1979) directed by Yuriy Norshteyn, were produced there - the latter hailed by the 1984 Animation Olympiad as the greatest animation film of all time. [3] Conversely it seemed, the same political conditions that had stifled art decades earlier, now served to support artists like Norshteyn. State-financed and free from commercial constraints, Soviet artists were able to indulge in diverse and labour intensive works that would have otherwise proved uneconomic.